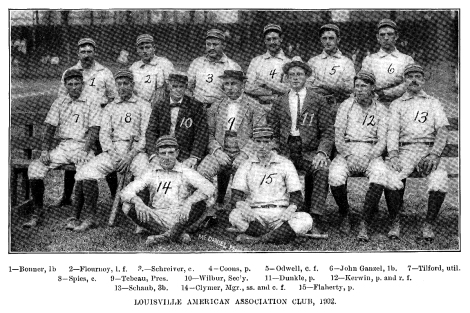

The 1902 Louisville Colonels

Several months ago the American Association Almanac realized that a substantial problem with respect to the early history of the American Association was the lack of information on players from the Louisville Colonels team. So the Almanac set about to remedy this by undertaking an overhaul of the roster listings already published in various sources. The primary aim was to determine accurate first names and to separate the Louisville record from the combined record for those players who spent their season with another team aside from Louisville. Among the more interesting highlights contained in this issue of the Almanac are:

1. The identification process for the Colonel player named Jimmy Hart as James Jeremiah Hart.

2. The effects of Louisville’s 1905 Trolley Car Crash in Kansas City

Below are excerpts from the latest issue of the American Association Almanac in which these, and a host of other topics, are discussed in this substantial and comprehensive look at the early history of this historic baseball club.

Idenifying “Jimmy Hart”

Hart’s case presents an interesting example of how a player’s records can be attributed to the wrong team, and it is often difficult to prove. Minor Leagues Database, lists Louisville’s Hart as “Hub Hart.” Initially his entry on the 1903 roster was taken at face value, but doubt crept in as additional information came to light. The June 6 Sporting Life contained the following phrase which conflicted with MiLD (Minor Leagues Database): “There is also a contention about Hart, late of Columbus…,” but it wasn’t immediately clear which Hart played with Columbus. This clue led to the temporary identification of this player as James Burton Hart based on information in MiLD. It was later shown that MiLD’s database had it wrong in this case as well.

The player in question is actually James Jeremiah Hart, born at St. Paul, Minnesota. For this player MiLD shows no record, but a listing in a 1904 Louisville Evening Post provided his middle name, which led to a search on ancestry.com verifying his occupation as a professional ballplayer. Additional information found in the Louisville Courier-Journal corroborated the information found in the Post; the latter also indicated his first professional team was Tacoma, possibly of the Pacific Northwest League in 1898, however, this could not be substantiated.

The confusion arose from the fact there are four entries for players by the name of “James Hart” listed in MiLD who could have been on the Louisville squad during this time period. The entry for James Burton “Burt” Hart was a possible match given his birthplace, listed as Lone Tree City, Minnesota (Brown County), a possible connection with his reported winter residence of Eau Claire, Wisconsin (given their geographic similarity). However, Burt Hart’s profile data didn’t match up with the information from either local newspaper.

One entry in MiLD, listed simply as “James Hart” (assigned the code “hart–001jam”). This entry contained no profile information, critical for comparative purposes, other than his name and the nine teams he played with from 1901-1911; hence, this entry was a sort of “wild card” as it was/is possible he was the player in question, based on his American Association ties via his reported affiliation with Columbus in 1902-03 and Minneapolis in 1903.

A “process of elimination” evolved as all available resources were considered. A look through the Almanac’s 1902 Columbus notes helped shed some light. A roster listing for the Columbus Senators published in the April 23, 1902 edition of the Columbus Citizen showed a “Jim Hart” at a height of 5’9.5” and a weight of 178; these figures corresponded with those in the Louisville Courier-Journal, thus connecting the Columbus Hart with the Louisville Hart.

The Almanac was then able to compare a clear facial photo from the March 30, 1902 Columbus Dispatch with a perfect studio image of the Louisville team players (without their caps on, greatly enabling the process of using a photo to ID players) from 1903. This process verified this was the same player, James Jeremiah Hart, as corroborated by a witness.

The 1905 Trolley Car Wreck in Kansas City, Missouri

As if the team hadn’t been through enough adversity, including what was described as a “narrow escape” from a railroad accident in June, a tragic event unfolded on the streets of Kansas City. On August 31 an accident with potentially fatal consequences took place involving several key players who had boarded a streetcar after the final game, an 8-2 win, of their final series against the Blues.

Eight of Louisville’s best had boarded the ill-fated trolley, bound for their hotel where they would prepare for a trip to Toledo. As the electric vehicle rode the rails toward Kansas City’s downtown it began to gather speed to an extent which alarmed the suddenly wide-eyed passengers. The trolley had no brakes! A terrific collision ensued which resulted in injuries to the eight Colonels. Those most seriously hurt were Ed Kenna (“the Pitching Poet”) and Bill “Hen” Clay, while Charlie Stecher, Roy Brashear, Larry Quinlan, Orville Woodruff (who had battled malaria), and manager Suter Sullivan were “badly bruised.” The men were taken shortly thereafter by ambulance to a hospital.

Within a few days it was reported that Brashear and Clay were mobile

only with the use of a cane, but that Stecher thought he’d be able to take his next turn on the hill. Quinlan expected to be back in action upon the club’s return to Louisville September 7.

Several days later Kenna was still recovering back in Kansas City. His

injuries consisted of two broken ribs, a wrenched left arm, and a “badly lacerated” face. The critical fear was that he could lose his left eye. The Louisville Times wrote, “All the players feel confident that Kenna will recover from his injuries and be able to play ball again next season, but state that he was badly injured in the wreck.” Edward Benninghaus Kenna was the son of Democratic U.S. Congressional Representative and Senator from West Virginia John Edward Kenna (by his second wife, Anna Benninghaus) who served in the U.S. Congress from 1883-93. The “poet pitcher” died of died of heart failure on March 22, 1912 at the age of 34; he was an editor of the Charleston (WV) Gazette.

The Times described the events as seen through the players’ perspective: “All the players place the blame for the accident on the motorman…They claim that the car was coming down grade at an excessive rate of speed and that the motorman did not ring the bell to give warning of the approach,” when it collided with another vehicle.

Stecher did not immediately recognize the extent of his injuries. According

to the Times, “Stecher stated that he did not know that he was injured until after he had reached the hotel, when he found that he could not walk.”

Clay may have escaped death. Hitting .378 and leading the league at the time of the accident, he sustained a “severely wrenched back,” and both his arms were in bad shape. He recalled being under the fender of the careening car, stating with some alacrity,

“It was then that I grabbed hold of the fender to protect my life. I certainly had an experience that I hope I will never again be so unfortunate as to have. I was dragged over fifty feet, and I was so rapidly losing my strength that if the car had not been brought to a standstill when it was I am certain that I would have been killed.

(Louisville Times, Sept. 4, 1905)

As Clay continued his wry retelling, he seemed almost lighthearted in delivering this articulate, yet sardonic, account:

“Say, but that certainly was a bad accident. It looked to me as though that motorman did not only want the right of the tracks, but also desired to take up the street. As soon as I struck the ground I saw the fender and ducked more adroitly than if Rube Waddell was sending one of his swift ones over the pan. It missed my head by the fraction of an inch and then I managed to get hold of the fender. Every step seemed hours and the torture was something terrific. I never thought that I would escape. When the car was brought to a standstill I managed to get out, and walked over to a fence and sat down on the grass.

I was bleeding from head to foot, and did not think that I would live more than a minute. Finally the motorman walked over to where I was sitting and, placing his hand on my shoulder, asked, ‘Are you hurt?’ Say, what do you think of that for nerve? It took me about five minutes to recover from that speech, and when I did, I said, ‘No, I don’t look like it, do I?’

I then asked the motorman why he didn’t ring the bell, and don’t you know that he has not answered me yet. Then I got up, staggered over the street curbing. The sound of the ambulance bell was like music. (Louisville Times, Sept. 4, 1905)

The Times detailed Clay’s status:

Clay is suffering from injuries all over his body. His hands are tied up, and it is all that he can do to walk around with the aid of a cane. Enough skin was torn off his hands, legs and face, in his long-distance slide, to cover every ball used in the American Association, according to his assertion. In Toledo he underwent an X-ray examination, and it showed he was badly injured, especially his hands.

Other players, and editors, looked back at the event with levity. As reported in the Times,

“Brashear says that he will never again take such chances as he did in that ride. ‘The next time I find a wagonette going fast where any car lines are near you will find me doing the duck act. Right out of the rear end for me.’”

If you’d care to learn more about how you can subscribe to the American Association Almanac, please contact me at pureout@msn.com or visit my website at www.americanassociationalmanac.com